Lions and Tigers and Flares, Oh My!

Last week I had two episodes of dyspareunia (pain with intercourse, or in this case, attempted intercourse - no way do my husband and I want to make the flare worse!) and dry vulvar tissues, a symptom that I have never experienced previously. WTF. More va-jay-jay drama.

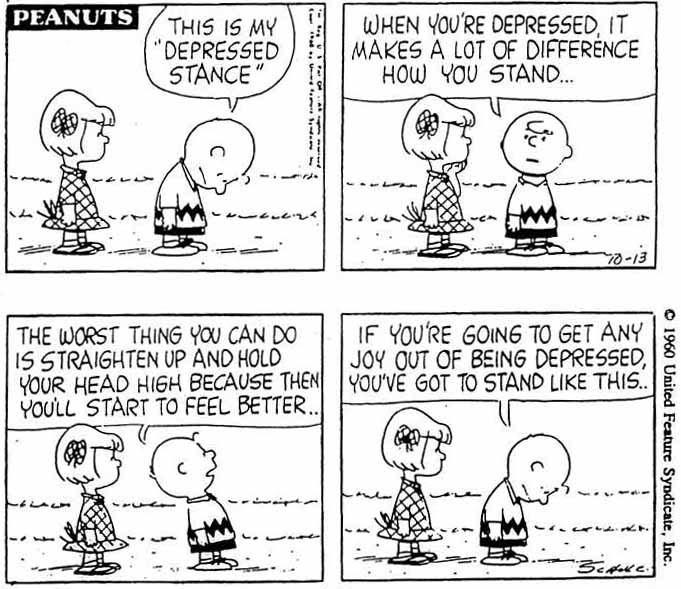

I briefly but deeply panicked, then reigned in the anxiety. I reminded myself that I have gotten over these humps before, and came up with some non-catastrophic theories about what could be happening.

The transition from my old meds to my new meds might not be as successful as I had initially thought. My hormone levels could be off. Maybe I was more anxious about some stuff going on in my personal life than I realized. Maybe I had a low-level yeast infection. All solve-able issues.

At any rate, I already had an appointment with my rocking' neurologist lined up for this week, and I quickly made an appointment with my gynecologist, who is thankfully well-versed in chronic vulvovaginal pain.

I figured between those two helpers I would be out of the woods in no time, and returned to a state of acceptance and calm.

My husband, however, did not.

The return of even this little bit of pain quickly dug up his old trauma. In his mind, all of our progress was lost and he was on the road back to a challenging sex life, feeling powerless to help a wife who would be in constant pain, dealing with this hell while struggling to manage his emotions AND be an emotional support to said wife, who would inevitably be freaking out.

Apparently my calm was not enough to keep him calm as well.

A snuggle and a chat was in order.

I reminded him that while I can't promise anything about the future, since we don't have a time machine he can't possibly re-live the past. I reminded him that he and I both have way more resources, supports, and skills than we used to. I reminded him that we have been through much worse, that I had two doctor's appointments only days away, and that as recently as this summer I briefly had pain that turned out to be nothing but a mild yeast infection that was easily and quickly treated...and followed by plenty of awesome sex.

* * *

This episode was a great reminder that chronic pain not only affects me, but also my beloved, especially since the pain affects our sex life.

In the early years I was so focused on my own suffering - and he was so good at hiding his own - that I didn't give much thought to what he was going through. It wasn't until a few years ago, when I had finally managed to pull together some quality help and was beginning to see improvement, that he began to open up about his struggles.

Our experience highlights the need for significant others to have a treatment plan of their own. Even though they are not physically hurting, their emotional roller coaster warrants support, both from professionals and the partner in pain.

And as for lions? Well, you might remember from the Wizard of Oz that they aren't always as scary as they seem at first...

(PS: For more thoughts on dealing with flares, check out this post from pelvicpainrehab.com)